The other day, my brother asked me about a proposal for a new recycling program in our city of Ottawa, Canada.

My brother really wants to know what I think. The new program, which apparently increases the responsibility of businesses and has them pay for the costs of recycling the packaging they produce. The program seems to have lots of support. Even the local green party member is tacitly supporting it (he says they should move faster with implementation). Since, I actually worked at a plastic recycling facility in Ottawa, and have been researching and thinking about the related issues for the last decade, this question has personal significance to me!

Me back at my stint working in a recycling factory in Canada. Read the essay I wrote afterwards.

On the surface it look like a great idea. Canadians are proud of their green tech and are genuinely and deeply passionate about ‘saving the environment’ and ‘going green’. It seems to cover the generally accepted criteria of what ‘green’ means. Perhaps the most compelling part of the idea is that the program aims to put the burden of the cost on industry. Those making the plastic can pay the cost of its processing. Consumers can keep consuming, governments can keep operating their same programs, and industry “can innovate like it does best” and keep doing what it is doing.

Our Dad is a historian. Our basement is full of history books and growing up we learned all sorts of stories about long ago battles and politics. The funny thing about history, is though it looks like things have changed with a new king, a new goverment, a new program, the actual reality keeps on going on.

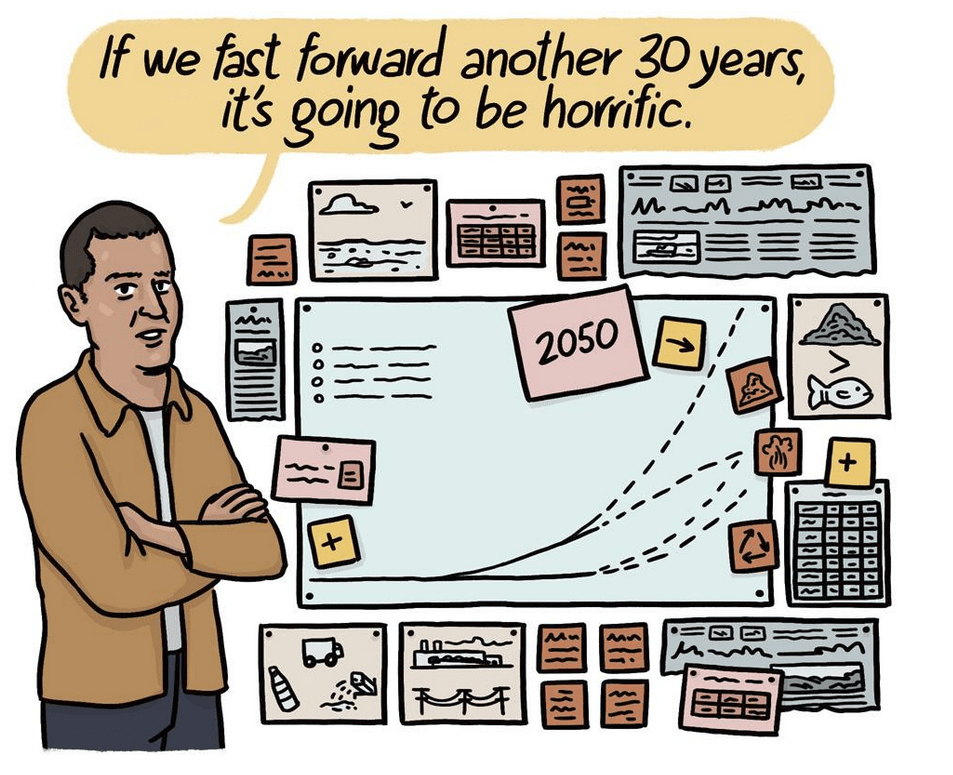

When you take a look at the history of recycling, its kinda the same. Despite all the new technology, programs and innovations, the net results over the last few decades haven’t changed much since the outset! Industry and government has been presiding over solutions for plastic and the results, as measured by scientists, are pretty clear: the vast majority of plastic eventually gets out loose into the biosphere.

The most broad meta-study of what has happened to our plastic over the last fifty years an estimated 8300 million metric tons (Mt) of virgin plastics have been produced worldwide; 9% of which have been recycled, 12% were incinerated and 79% have accumulated in landfills or the natural environment.1 If my brother had gotten 11% on one of his tests, I would have been pretty disapointed in him!

Ok, so that’s the plastic getting into the biosphere. But there’s something even more disconcerting that has stayed the same. The concept of recycling, as developed and delivered to us by industry, systematically decrease our collective ecological awareness over the decades.

Ok, so that’s the plastic getting into the biosphere. But there’s something even more disconcerting that has stayed the same. The concept of recycling, as developed and delivered to us by industry, systematically decrease our collective ecological awareness over the decades.

Growing up in the land of the Northern Tutchone people of the Yukon back in the 80’s, when we threw it away, we knew exactly where it was going. In fact, the highlight of our month was the regular trip to local dump where we my brother and I would help our Dad lug it out ourselves. The dump was surrounded by forest, and we’d often see bears, eagles and other animals scavenging. I like to think it gave us some mindfullness of our consumption and throwing away.

BBC: UK Recycling ending up in Malaysia

Today, no one has any idea where the plastic they use goes. When I worked at the local Ottawa recycling facility, between shifts, I asked my foreman where they various bales were going. He shrugged, “India, China– somewhere in Asia”. Even he didn’t really know!

Up until 2017, most of the folks in the UK who happily assumed that their council and industry were taking care of their plastic– until David Attenborough and other investigative journalist showed them pictures of their UK plastic (often still their town’s labelled recycling bag) kicking around in vast south east asian dump sites.

Will increasing the efficiency of Ottawa recycling make it work? Will imposing responsibilities on plastic producers make them more responsible? Will having business invest more in recycling and plastic technology save the day? While these may sound fantastic, its good to remember similar proposals and promises over the last thirty years and compare them to the results.

Sure it will help… a little.

But, according to Roland Geyer, the scientist who wrote the plastic survey study I quoted above, if we keep going with just little amendments to our direction, we’re still effectively headed in to the same place: “Without a sea change in industrial habits, this is our lasting legacy”.

But, according to Roland Geyer, the scientist who wrote the plastic survey study I quoted above, if we keep going with just little amendments to our direction, we’re still effectively headed in to the same place: “Without a sea change in industrial habits, this is our lasting legacy”.

How come? I observe that one thing that industrial systems have in common is an experiential disconnect from ecological consequences. By giving all the responsibility to government and industry, we loose connection with the consequences of our consumption and disposal. We loose an innate awareness of our connection to local and global ecologies.

My friend Pak Har, who is the CEO of a large Indonesian juice corporation, is extremely conscious of his company’s plastic production. His company sells packaged juice products which produces about 2000 tons of non-recyclable plastic which go loose into the Indonesian biosphere every year. He told the story of attending a family wedding of the owner of the company that supplies him the plastic for his products. At the wedding, Pak Har bumped into the owners suppliers. He was shocked to discover that they were executives and representatives from the biggest names in oil corporations.

Funnily, enough, this is what I would call an ‘ecological experience’. Pak Har had heard me talk about the connection between plastic and petroleum and he’s given it tons of though himself, but the deep realization didn’t occur til he experienced it first hand.

When we consume plastic, we’re connecting to a much deeper system of petroleum derived energy and petroleum based capital. When this moves around it has ecological consequences far broader than our landfills and recycling plants. As all this plastic moves from company to company, industry to industry, much energy is expended along the way. The CO2 emissions of managing, moving and recycling plastic have become more and more significant. In fact, by 2030, CO2 emissions from the production, processing and disposal of plastic could reach 1.34 gigatons per year—equivalent to the emissions released by more than 295 new 500-megawatt coal-fired power plants.4

Yikes.

So what to do back in Ottawa? Is the enhanced recycling program a good and green idea?

My apologies Ed, but with all that said I am going to avoid directly answering the question. Maybe that little discourse, gives you some intutions, however, I will be the first to admit that such meta-critique doesn’t help anyone. It doesn’t assist the green party candidate in his evaluation, it doesn’t help the companies in their new task, nor the citizens in theirs. At best it gets people depressed and feeling cornered by the impossibility of the challenge.

For me there is a much more important and pressing question. And more helpful.

What does “green” mean exactly? What in fact is an ecological contribution?! The folks making the decisions in Ottawa have the best of intentions, the funds and the political backing. What strikes me though, is that for all their good intentions, they are missing an adequate framework to make a proper evaluation of how to manage Ottawa’s plastic in a way that is an authentic contribution to the greening of the biosphere.

That green party candidate, his top priority is surely ecological concerns, yet his evaluation of the recycling options falls into relatively simplistic criteria: “How much plastic can we divert from landfill?” “How much of the funding can be taken in by industry rather than the government?” “How much responsibility can we put on manufacturing?” “How much can we reduce the city’s recycling budget? (so they that can spend it on other green stuff)”.

Since, my background is in philosophy, with a love ethics, this is where I think I can best assist.

Given the connection of plastic to a much deeper system and story, I think we all want a deeper evaluation than one that is purely economic and quantitative. And not just for Ottawa’s recycling program, but also waste to energy technologies, cleaning up the ocean, bioplastics, etc.

How do we do this?

I believe we need a new, impartial, non-ethical, ethics for making the evaluation.

Hold on… non-ethical ethics?

Yep, that’s right– whereas traditional ethics has concerned itself with the good/bad. righ/wrong of human relations and enterprise, we’re now far beyond that. The green party candidate, Pak Har, my brother, me… we all want to do the best thing for the Earth– and so in this sense we’ve moved beyond the ethical analysis of the last century– when ecological impacts were not of concern or consequence.

Stay tuned. I happen to have been working on this for the last year and am excited to share a new major essay on this. I am poised with a Copernikan level breakthrough! If you’re in a rush check out the preliminary conceptual infrastructure that we’ve been laying over the last few months.

———————

1Geyer, Jambeck and Lavender,’Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made’, (Science Advances)

2Matthew Taylor, ‘$180bn investment in plastic factories feeds global packaging binge‘, (theguardian.com, 26 Dec 2017)

3Geyer, Jambeck and Lavender,’Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made’, (Science Advances)

4Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet, Center for International Environmental Law, Executive Summary, May 2019